Saving the African grey parrot: the battle to beat the pet smugglers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The first thing to know about the African grey parrot is that it is not entirely grey. The medium-sized bird, which lives in forests in west and central Africa, has electric-red tail feathers that make it a target for poachers, who use the plumage for ceremonial headdresses. Its body parts are used in traditional medicine.

Unfortunately for the African grey, these are the least of the species’ problems. A highly intelligent animal capable of mimicking human speech and which can live in captivity up to the age of 60, it has also been a sought-after pet since biblical times.

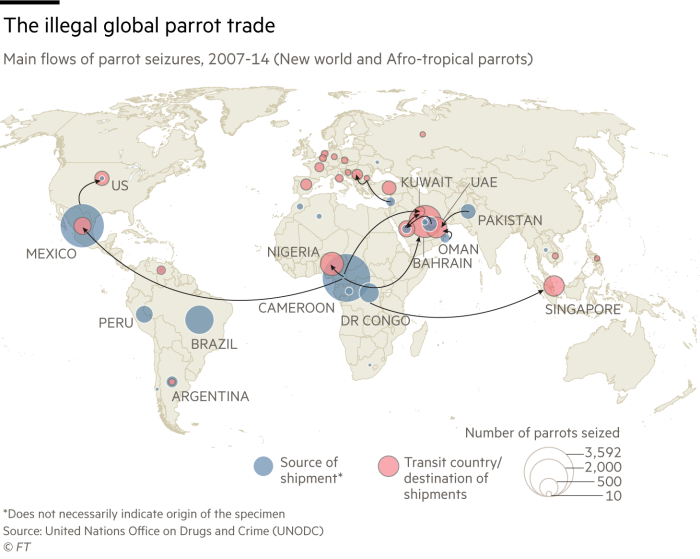

In an era when the international pet trade has reached industrial proportions, the demand — from the Middle East and Asia as well as Europe and North America — threatens the African grey’s long-term existence in the wild.

The parrot inhabits a strip of equatorial forest that runs from Ivory Coast through Nigeria, Cameroon and Gabon and into the Democratic Republic of Congo. In Ghana, where poaching has been intense, the population has fallen more than 90 per cent since the early 1990s, according to estimates. Numbers of birds in other countries are difficult to gauge, but experts at the Zoological Society of London, the FT’s Seasonal Appeal partner for 2019, say they are falling sharply.

So acute has the problem become that the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) outlawed trade of the African grey altogether in 2016. Before the ban, about 1.3m parrots had been exported legally since 1980, according to estimates, excluding the hundreds of thousands that likely died during trapping and transportation.

Conservationists are divided over the efficacy of the ban. Samuel Nebaneh, a law enforcement co-ordinator in Cameroon, which has a large population of grey parrots, welcomes it. “It has had a positive effect. Some parrots have been seized and traffickers have been sent to trial,” he said.

Others say the ban has driven up prices, and therefore the incentive to poach, as well as prompting trappers to use longer smuggling routes where the birds are more likely to die en route. An African grey can retail for £1,000.

Pamela Watson, an author who kept two African greys when she lived in the Nigerian city of Lagos, said the Cites ban was inadequate without work at village level to give people alternative incomes.

“They’re not able to stop it because the traffickers are armed. This is a huge business. There are international gangs behind this,” said Ms Watson, who now lives in London and has been unable to obtain an export licence for her parrots, which remain with friends in Lagos. After having the parrots for years and realising how intelligent they were, she said, she would not now advocate keeping them in captivity.

In 2014, Mr Nebaneh encountered a Ghanaian poacher in south-west Cameroon who had been exporting trapped birds in batches of 500.

In Cameroon, parrots are caught in forest clearings where they congregate in huge numbers. Trappers take advantage of their sociability, smearing glue on to palm fronds and branches and tethering decoy birds, which call out and attract victims to the area. The parrots become stuck and many perish through lack of food and water before trappers come to collect them. Sometimes hunters cast nets over whole flocks.

ZSL is working with authorities in Cameroon to try to halt smuggling, intervening at all levels of the supply chain. It sets up camera traps to monitor wild populations, works with local communities to discourage poaching and provide alternative livelihoods, and helps train eco-guards and border officials to recognise and stop the trade.

When birds are seized, as well as helping authorities prepare for trial through expert witnesses and record keeping, ZSL teaches eco-guards how to care for the birds and return them to the wild.

Hauls of 100 or more are not uncommon, but all too often the parrots, malnourished and traumatised, die before they can be rehabilitated.

Gary Ward, curator of birds at London Zoo, visited Cameroon’s Dja reserve in November to help eco-guards care for seized parrots, including providing appropriate aviaries and food supplements. “The husbandry training is pretty basic,” he said. “We’re not trying to train them how to breed the parrots, just to keep them alive.”

Eleanor Harvie, ZSL’s programme manager for Africa, said the eco-guards were easy to motivate, as it was more rewarding to seize live birds than, say, the tusks of an elephant or the scales of a pangolin that had already been killed. While understanding of the parrots’ numbers in the wild remained sketchy, she said, there might be enough to make preservation a realistic goal.

Grant Miller, who until recently worked for the UK Border Force and is now a counter-trafficking adviser to ZSL, has direct experience of the exotic pet trade. “They’re like stamp collectors,” he said of those who order rare species. “I want what I haven’t got.”

Mr Miller remembers rushing to Heathrow airport in June 2018 after receiving a tip-off from Interpol that a man named Jeffrey Lendrum was arriving on a flight from Johannesburg. “He was the Pablo Escobar of the bird world,” said Mr Miller of a man who had been arrested numerous times on bird smuggling charges.

On this occasion, Mr Lendrum was nabbed with 19 eggs and two newly hatched chicks secreted in a heavy jacket. The fish eagle and kestrel eggs, whose trade was banned, were worth between £2,000 and £8,000 each.

Grey parrots are not yet as rare or as endangered. ZSL, said Mr Miller, was hoping to keep it that way.

Notable wildlife seizures in the UK

- This year, London Zoo put on a display a Chinese giant salamander, named Professor Lew (pictured). The salamander, then considerably smaller, had been smuggled into the country three years earlier along with four others in a cereal box, but was intercepted by the postal service.

- A 23-year-old man was jailed for six months after trying to smuggle more than 700 rare and endangered corals and clams through Manchester airport. The corals, now being looked after by ZSL, had been brought from Vietnam.

- Officials at Heathrow Terminal 5 in 2014 intercepted 13 rare San Salvador rock iguanas in a suitcase on a plane from the Bahamas. Each iguana was stuffed into a sock. Twelve had survived the journey.

- In 2017, a 64-year-old man was caught trying to smuggle 600,000 live glass eels with a street value of £1.2m to Hong Kong. There is an EU ban on exports of the eel, which is a delicacy in Asia.

- Jeffrey Lendrum, a former special forces soldier also known as John Smith, was this year sentenced to jail for three years after being intercepted at Heathrow airport with 19 rare birds eggs, worth up to £100,000 in total, strapped to his body. Most of the eggs went on to hatch.

Follow David Pilling on Twitter: @davidpilling

How you can help

Please help us support ZSL’s urgent work through the FT’s Seasonal Appeal. Your donation will help tackle a range of threats to wildlife across the world through science, education and conservation. Click here to donate now.

If you are a UK resident and you donate before December 31, the money you give will be matched by the UK government — up to £2m. This fund-matched amount will be used by ZSL projects to help communities in Nepal and Kenya build sustainable livelihoods, escape poverty and protect their wildlife.

Read more about our Seasonal Appeal partner ZSL: ft.com/zsl-facts

Comments